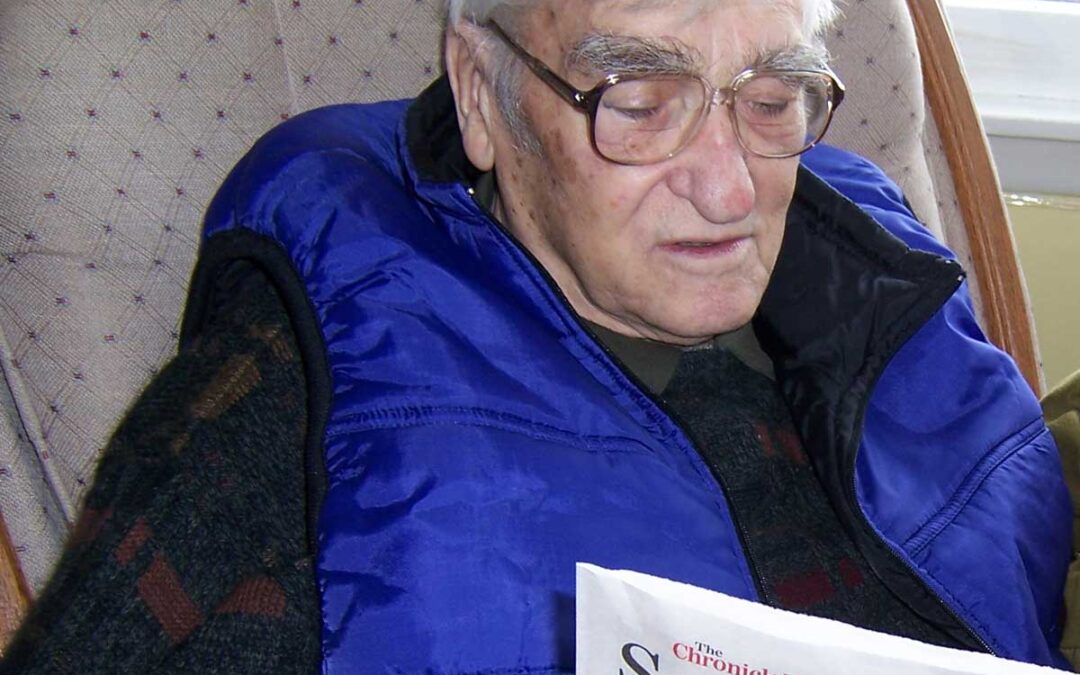

My father read the obituaries every day.

I would hear him mumble, “Well, he’s gone.” Or, “Oh look, she died.”

Eventually, more of the people he had ever known were on the other side of Death’s door than on this side.

It must have made it easier for him to contemplate that transition himself. Indeed, he welcomed it when it came. He was ready.

When I used to hear old people say things like: “I’m ready, Lord, come take me,” or “I’m afraid God forgot me,” I wondered how they could accept or even welcome their impending death.

I couldn’t imagine myself feeling ready or willing to die.

In her 90s, my grandmother said that inside, she still felt like the young girl she had once been. Her sense of self hadn’t changed despite her aging body.

And indeed, there is a core of the self that never changes.

Finding that rock-solid sense of being, independent of actions, perceptions, accomplishments, state of health, possessions and relationships, is one of the goals – and rewards – of a meditation practice.

My grandmother put off dying as long as she could until, bedridden and with dementia, her body gave out at 98.

Was she even aware that she was old? Maybe in her mind she was still that young girl.

My stepfather was more aware. After surviving a heart attack in his 70s, he explained his new weakness in his mid-Atlantic accent, “One is not what one was,” and accepted his limitations while continuing to live as fully as possible.

Years later at 92, when cancer showed him the inevitable end, he embraced it. “I’ve had a good run,” he said, as he saw to the dispersal of his remaining possessions.

Lately, as my own body grows older and feels more limitations, I’ve thought about how aging prepares us for death in the most natural of ways.

Because we’re all enrolled in a course you could call the Yoga of Life.

Those who are fortunate to live a long life, even if they do not pursue meditation or spiritual studies, experience the natural falling away of whatever they have become attached to.

The body falls apart, the career ends, the family home is sold, youthful ambitions remain unachieved, friends and family members pass, whatever fame or notoriety you had is forgotten (along with where you put your reading glasses), and old grudges fade along with unrequited passions.

The mantra of the meditation student becomes one’s reality. I am not my body. I am not my possessions or my achievements. I am not my thoughts. I am not my emotions. I am not my beliefs.

The sense of beingness is all that’s left.

And that can prepare a person for the transition as surely as years of meditation practice.

Heather is a Quantum Healing Hypnosis (QHHT, BQH) practitioner, working with clients online and in person in Mahone Bay, Nova Scotia.